BadB

Professional

- Messages

- 1,883

- Reaction score

- 1,922

- Points

- 113

The primary goal of ATM security analysis is to identify theft scenarios that can be carried out by hackers of various origins (external or internal, such as bank technical staff) and levels of training: from a casual attacker using off-the-shelf malware to a service engineer with knowledge of the ATM's internal structure and extensive access to the equipment.

Additionally, scenarios for intrusion into a bank's network due to insufficient protection of the bank's perimeter can be considered. These scenarios are formed from configuration flaws and vulnerabilities discovered by ethical hackers, which arise at various levels of ATM operation. Afterwards, specialists provide recommendations that allow companies to protect their devices from unauthorized access.

To better understand all of the above, we will first (in the first part of the article) examine the design of ATMs and discuss the main types of attacks on them. Then (in the second part), we will examine some of the current types of ATM attacks and provide recommendations for preventing them.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute instructions or a call to commit illegal acts. Our goal is to highlight existing vulnerabilities that can be exploited by attackers and to provide recommendations for protection. The authors assume no liability for the use of this information.

First, let's make a small digression into the history of the issue.

That very first ATM (source: Google Images)

Although ATMs have evolved from simple cash dispensers to sophisticated multifunctional devices since 1968, they remain a magnet for thieves. An ATM is a quick access point for large sums of money, and the number of devices makes them significantly more difficult to protect: many ATMs are located in uncrowded areas with 24-hour operating hours (for example, at gas stations). Therefore, historically, increased attention has been paid to protecting ATMs from physical attacks — modern devices can weigh over half a ton, and various sensors (position, temperature, drawer opening, and so on) are installed inside the device.

But while the safe inside the ATM offers the best protection against tampering, we estimate that the level of protection against intrusion into the control equipment area remains low. This makes the ATM vulnerable not only to physical attacks but also to logical attacks, which have become increasingly popular among hackers.

According to Cisco Talos, a growing number of new malware variants targeting ATMs have been detected since 2009. While the total number of detected samples remains relatively small compared to other malware categories, this trend has had consequences: in 2020 alone, 269% more logical attacks on ATMs were registered in Europe compared to the previous year. Remarkably, the average damage increased almost a thousandfold, from relatively modest amounts of under a thousand euros to over a million euros.

As a result, ATM malware is no longer an exclusive product. This has led to a reduction in its price on marketplaces and a lower barrier to entry for attackers. The Cutlet Maker malware, discovered in 2017, came with detailed instructions in Russian. These included troubleshooting tips for issues that may arise when using the software on various ATMs.

A fragment of the instructions supplied by the attackers with the Cutlet Maker malware (source: Trend Micro)

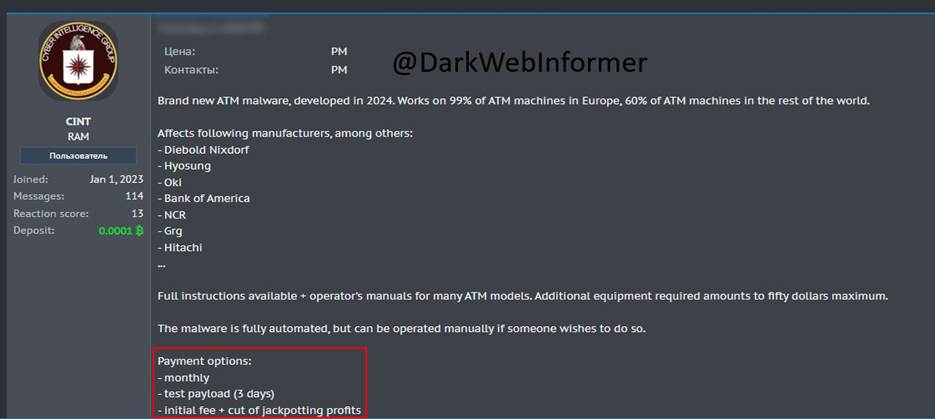

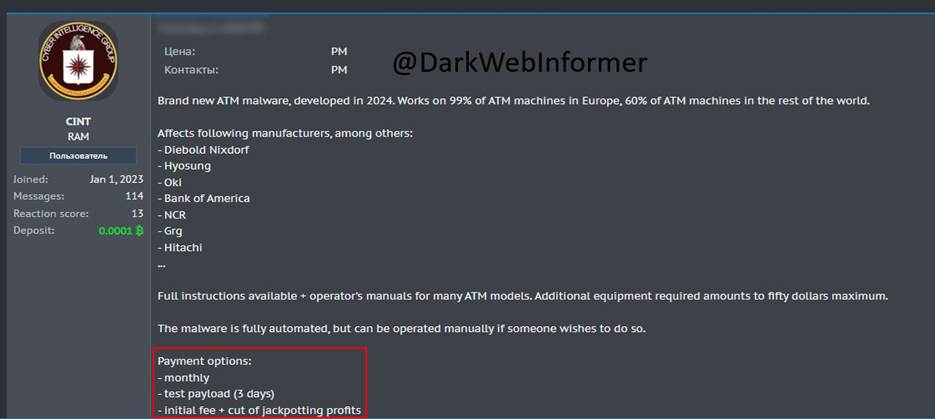

And already in 2024, offers for the sale of VPO with several convenient payment options, including a monthly subscription, appeared on trading platforms.

ATM software with three payment options (Source: x.com/DarkWebInformer)

The main drawback of logical attacks is their complexity — which is why their prevalence is significantly impacted by the spread of malware and the subsequent lowering of the barrier to entry for criminals. However, a key advantage of logical attacks is that they are more undetectable than physical attacks and often allow attackers to repeatedly replay an already infected device. It's also worth remembering that modern ATMs are increasingly equipped with vandal-resistant cassettes: if any physical attack occurs on these cassettes, the ATM contents are permanently coated, making further use of the cash impossible.

Financial losses from attacks continue to grow both globally and regionally. By the end of 2023, global direct losses to banks from ATM fraud reached US $2.4 billion. Europe lost €173 million during the same period , €67 million of which came from skimming-related attacks. The problem remains particularly acute for the United States: despite accounting for only 25.29% of global transaction volume, American banks incurred 42.32% of global losses. This disproportion is due to the fact that traditional fraud methods, such as skimming, remain a significant threat in many countries. In 2023, 45% of all ATM fraud cases were related to skimming, resulting in losses of over US $900 million in North America alone. More than 315,000 cards were compromised, affecting at least 3,000 financial institutions.

The increasing activity of criminals is naturally driving growth in the ATM security solutions market. According to the Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Security Global Market Report 2025, the global ATM cybersecurity market has grown from $17.77 billion in 2024 to $18.91 billion in 2025, with a compound annual growth rate of 6.4%. Experts attribute this growth to several factors: the increasing number of ATMs worldwide, the increasing sophistication of cyberthreats, and stricter regulatory requirements for financial services security.

However, the approach to device security remains uneven. Physical security measures remain a priority for many banks, while protecting the underlying hardware — operating systems, drivers, and control software logic — often falls by the wayside. This creates serious risks: according to a 2022 study by RTM Group, it's possible to penetrate an ATM without activating an alarm in every other case, allowing an attacker to interact with the equipment unhindered. Underestimating these logical risks leaves many devices vulnerable to attacks that require little skill and can cause significant damage in a short period of time.

Meanwhile, financial technology is constantly evolving, fueling new attacks: in the US alone, losses from cryptocurrency ATM fraud in the first half of 2024 amounted to $65 million. In the face of rapidly evolving threats, a comprehensive approach to ATM security, combining physical and software protection measures, is becoming essential to ensure the resilience of the financial infrastructure.

It's worth noting that the diagram describes a specific case discussed in this article and does not represent the default configuration, which may vary from device to device. Now let's examine each stage in the diagram, from card presentation to withdrawal or deposit. To do this, we'll imagine each stage as a separate level of ATM operation, each with its own set of tasks.

1. User level (input devices and kiosk application)

For convenience, individual components and internal processes of an ATM can be thought of as operating at different levels.

User interaction with the device is limited to presenting a card and selecting a transaction. Previously, the only way to access an ATM was by inserting a card into the card reader. Back then, attacks aimed at intercepting card data, such as skimming and shimming (the obtained information was used by criminals to create duplicate payment cards), were widespread. Today, such methods have become largely obsolete in Russia thanks to the implementation of additional security mechanisms and the decline in the percentage of ATMs vulnerable to these attacks.

With the spread of contactless cards, ATMs have added NFC (near-field communication) readers to their card readers. Some ATMs even eliminate the need for a card: a one-time QR code is used, either generated on the ATM screen and scanned in the bank's mobile app, or generated in the app and scanned by the ATM.

To protect against unauthorized access to the card, a PIN code is additionally requested. The PIN code is entered using an encrypted PIN pad (or keypad), which consists of a keypad and a cryptographic module. This ensures that the PIN code is not transmitted or stored in plain text. Verification of the PIN block (the encrypted PIN code value) is performed by the processing center. It is worth noting that modern ATMs that implement mini-office functionality (more on this below) may additionally verify the customer's identity before processing — for example, using biometric modules of facial recognition technology.

After verifying the customer's identity, the ATM prompts the user to select a transaction: cash withdrawal, balance view, funds transfer, or other. Although the ATM contains a standard computer, the user cannot fully interact with it. All necessary functions are provided by a single full-screen banking app running in kiosk mode.

2. OS level (control software and security tools)

As mentioned earlier, an ATM is housed within a standard computer. Let's examine the processes that occur at this level, without discussing the cash dispensing equipment for now.

The part of the ATM that houses the computer is called the service area. This area is separated from the outside world by a flimsy door secured with a simple lock. However, devices of the same series often use a single key, which can be purchased online.

In addition to the system unit, the ATM's service area houses network equipment and connections for the ATM's peripheral devices (card reader, readers, PIN pad, and dispenser). Communication between the peripheral devices and the system unit is via USB, Ethernet, PCI, or COM interfaces.

ATM computers most often run Windows. While Windows Embedded was previously the predominant operating system, Windows IoT (based on Windows 10 and used in embedded systems) is now more common. Furthermore, as part of import substitution efforts, an increasing number of ATMs are being converted to Linux-based operating systems.

A Windows ATM (source: Reddit)

In addition to the banking application running in kiosk mode, the OS also includes ATM management software and security features, such as:

A key component at the OS level is the control software (CSS). Previously, CSS was developed by ATM manufacturers, which led to compatibility issues when using equipment from different vendors in a single fleet. However, with the spread of the CEN/XFS hardware management standard (more on this below), universal solutions have emerged that allow for the management of devices from different manufacturers. Currently, most ATMs use multi-vendor CEN/XFS-based CSS, which ensures the best compatibility and enables unified maintenance of a diverse fleet of devices.

Although the primary functions of the ATM management system are managing ATM peripherals and interacting with the processing center, depending on the implementation, it may include a number of additional features. For example, it may include software for a monitoring server, which allows for remote management of the self-service device network. To facilitate physical ATM maintenance, additional features (such as quick access to diagnostic utilities from a separate menu) can be implemented in supervisor mode, accessible only to technical staff.

3. Network level (data exchange with the processing center and remote monitoring server)

After selecting an operation, it's necessary to check its feasibility. The decision is made by the processing center — a server on the bank's internal network that checks:

To prevent interception and modification of the processing center's responses, data exchange between the processing center and the ATM is protected by encryption, most often using a VPN connection. NDC or DDC are often used as the messaging protocol, having become the unofficial standard for communication with the processing center even before the advent of multivendor UPR. Furthermore, the ISO 8583 standard and its modifications are also widely used. It's worth noting that UPR vendors can develop their own protocols for data exchange with the processing center, while maintaining support for standard protocols to ensure backward compatibility.

In addition to the processing center, the ATM can communicate with a monitoring server, which is used for remote management, device status monitoring, and downloading updates. Unlike communication with the processing center, this type of communication is often not encrypted.

4. Firmware level (data exchange with equipment)

After receiving confirmation from the processing center, the UPO initiates data exchange with the cash dispenser or the cash acceptance module (depending on the selected transaction). At this level, interaction occurs with devices that, in the vast majority of ATMs, are located in the most secure area — the safe area. In addition to the dispenser, the safe may also house a recirculation module (in some cases, this equipment is partially located in the service area). Unlike the service area, which houses the rest of the peripheral equipment, the safe area is made of more durable materials and has a separate key.

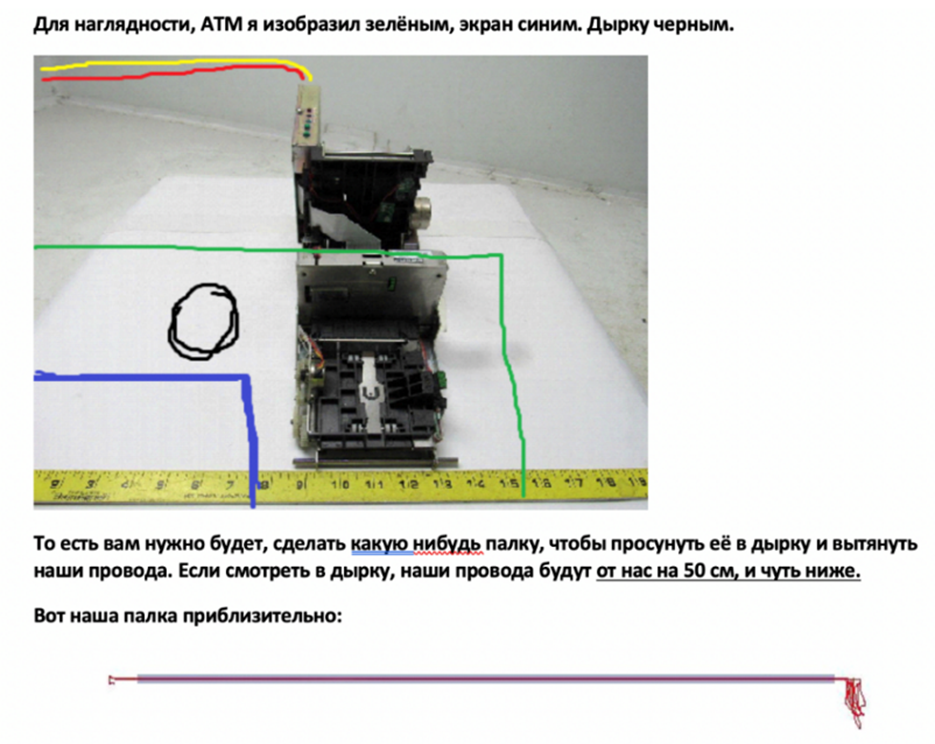

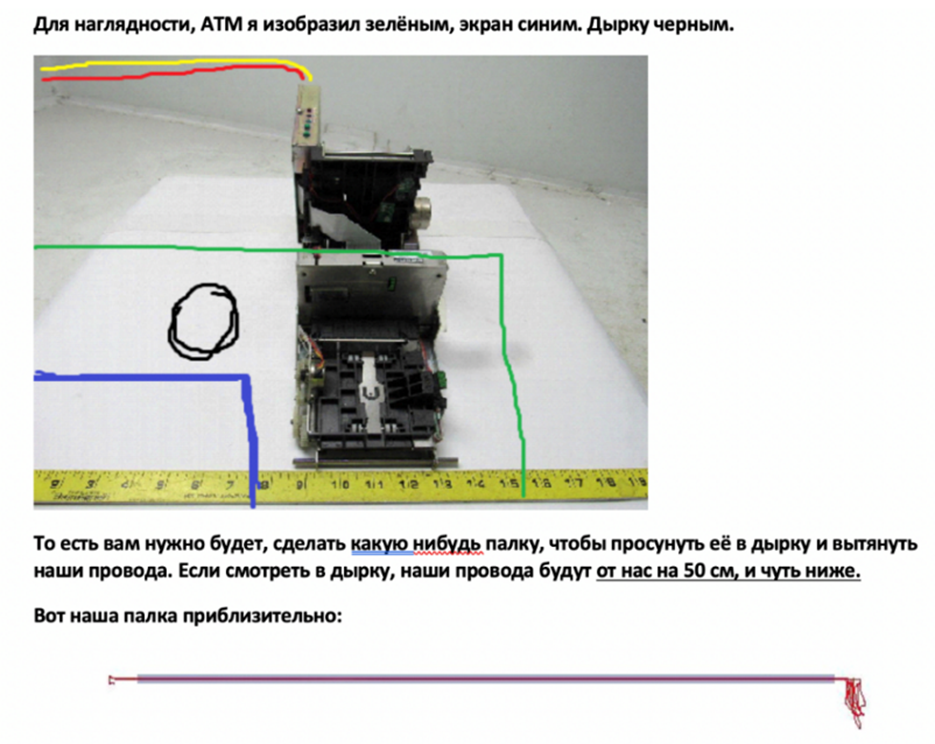

A dispenser (without cassettes) in an ATM safe (source: LiveJournal)

Hardware management is implemented according to the CEN/XFS standard, which describes a client-server architecture consisting of a hardware manager (XFS Manager) and service providers (Service Providers). The hardware manager API is implemented by the UPO, and a service provider is a driver containing a set of standard functions for managing and retrieving information about a peripheral device — for example, a dispenser, card reader, or cash acceptance module.

To dispense cash, the dispenser selects the required number of bills from the ATM cassettes, moves them to the cash tray, and opens the shutter (a flap that restricts access to the cash tray). Data transmitted between the ATM and the dispenser can be encrypted, and authentication is performed before the exchange to prevent device substitution. Encryption and authentication algorithms are implemented by the dispenser's built-in firmware.

When cash is deposited, banknotes are verified by a validator. This procedure is especially important for ATMs with a recirculating function, which constitute the majority of the ATM fleet. Unlike traditional machines that only dispense cash, these ATMs can recycle banknotes previously deposited by other users. This increases the importance of accurately detecting counterfeit bills.

Physical attacks are aimed at directly affecting the ATM or its components. The goal is to extract funds or interfere with the normal operation of the device without resorting to software. These are traditional attacks that ATMs have been subjected to long before the advent of targeted malware. These attacks require no specialized knowledge, and some target not the ATM itself, but its users.

Unlike physical attacks, logical attacks require specialized skills and greater technical expertise from the perpetrator: they exploit vulnerabilities in the ATM software and its network environment. Despite their complexity, these attacks attract less attention and allow repeated attacks on the compromised ATM to re-profit, making them the most dangerous for banks.

The job of security analysts is to identify software vulnerabilities that enable logical attacks. Therefore, in this article, we won't focus on physical attacks, but will instead focus on logical attacks. These are divided into two categories: system and network.

System attacks are aimed at exploiting functions or altering the logic of applications running on the ATM operating system. The goal of such attacks is to extract funds or bypass security mechanisms. Blackbox attacks are particularly common: while most attacks in this category require the hacker to first gain access to the operating system, a blackbox attack involves connecting the attacker's device directly to the dispenser. It's important to note that blackbox attacks can also be carried out on other ATM peripherals (for example, the banknote validator). This article will focus specifically on interaction with the dispenser.

Network attacks target ATM network components. Hackers may attempt to intercept, forge, or otherwise manipulate data transmitted over the network, or gain remote control over the ATM. The greatest danger comes from attacks targeting the processing center: if security is inadequate, a hacker can forge responses sent to the ATM and perform cash withdrawals even if they were rejected by the processing center.

It's important to understand that most system and network attacks require access to the equipment in the ATM's service area. During a security assessment, security specialists are granted this access by default; a hacker can gain access by drilling a hole in the ATM's casing or by picking the lock on the service area door. It's also important to remember that a key to the service area can sometimes be purchased online or obtained from an insider — for example, a technical engineer who maintains the ATM's equipment.

Only some of the attacks described result in cash withdrawals; the remaining attacks represent intermediate steps toward this goal. For example, an attacker might seek to gain remote control of an ATM over the network and then develop an attack at the OS level using methods classified as system attacks. A matrix can be used to represent the interrelationships, reflecting the possible transitions between attacks that would allow for a complete cash withdrawal scenario.

Below is an example of such a matrix: an arrow in a row indicates the transition to an attack in the corresponding column, and a check mark reflects the possibility of the attacker receiving funds as a result of the attack.

Here's how you can use the matrix to build a money disbursement scenario:

Some columns lack arrows, indicating that a hacker only needs access to the ATM's service area to carry out an attack. For example, accessing the hard drive requires no additional steps: this action could be the first step in a full-fledged theft vector.

A matrix can provide a general idea of possible cash dispensing scenarios, but the real fun lies in the details. Therefore, in the next chapter, we'll examine the most common ATM attacks encountered by our banking security researchers.

(c) Source

Additionally, scenarios for intrusion into a bank's network due to insufficient protection of the bank's perimeter can be considered. These scenarios are formed from configuration flaws and vulnerabilities discovered by ethical hackers, which arise at various levels of ATM operation. Afterwards, specialists provide recommendations that allow companies to protect their devices from unauthorized access.

To better understand all of the above, we will first (in the first part of the article) examine the design of ATMs and discuss the main types of attacks on them. Then (in the second part), we will examine some of the current types of ATM attacks and provide recommendations for preventing them.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute instructions or a call to commit illegal acts. Our goal is to highlight existing vulnerabilities that can be exploited by attackers and to provide recommendations for protection. The authors assume no liability for the use of this information.

First, let's make a small digression into the history of the issue.

The history of ATM attacks

The first operational ATM was installed in London on June 27, 1967. It had no balance check feature (therefore, the maximum transaction amount was limited to £10) and dispensed cash only, accepting special cheques. By 1968, an enterprising Swedish engineer had discovered a way to decipher customers' PINs. This allowed him to travel the country withdrawing kronor from ATMs until he was stopped by the police.

That very first ATM (source: Google Images)

Although ATMs have evolved from simple cash dispensers to sophisticated multifunctional devices since 1968, they remain a magnet for thieves. An ATM is a quick access point for large sums of money, and the number of devices makes them significantly more difficult to protect: many ATMs are located in uncrowded areas with 24-hour operating hours (for example, at gas stations). Therefore, historically, increased attention has been paid to protecting ATMs from physical attacks — modern devices can weigh over half a ton, and various sensors (position, temperature, drawer opening, and so on) are installed inside the device.

But while the safe inside the ATM offers the best protection against tampering, we estimate that the level of protection against intrusion into the control equipment area remains low. This makes the ATM vulnerable not only to physical attacks but also to logical attacks, which have become increasingly popular among hackers.

According to Cisco Talos, a growing number of new malware variants targeting ATMs have been detected since 2009. While the total number of detected samples remains relatively small compared to other malware categories, this trend has had consequences: in 2020 alone, 269% more logical attacks on ATMs were registered in Europe compared to the previous year. Remarkably, the average damage increased almost a thousandfold, from relatively modest amounts of under a thousand euros to over a million euros.

As a result, ATM malware is no longer an exclusive product. This has led to a reduction in its price on marketplaces and a lower barrier to entry for attackers. The Cutlet Maker malware, discovered in 2017, came with detailed instructions in Russian. These included troubleshooting tips for issues that may arise when using the software on various ATMs.

A fragment of the instructions supplied by the attackers with the Cutlet Maker malware (source: Trend Micro)

And already in 2024, offers for the sale of VPO with several convenient payment options, including a monthly subscription, appeared on trading platforms.

ATM software with three payment options (Source: x.com/DarkWebInformer)

The main drawback of logical attacks is their complexity — which is why their prevalence is significantly impacted by the spread of malware and the subsequent lowering of the barrier to entry for criminals. However, a key advantage of logical attacks is that they are more undetectable than physical attacks and often allow attackers to repeatedly replay an already infected device. It's also worth remembering that modern ATMs are increasingly equipped with vandal-resistant cassettes: if any physical attack occurs on these cassettes, the ATM contents are permanently coated, making further use of the cash impossible.

Brief statistics of attacks

From 2019 to 2022, the number of ATM-related crimes increased by 600%, with a 165% increase from 2021 to 2022 alone. This increase was driven by both the increase in logical attacks and the rise in physical attacks on devices (which traditionally account for the majority of all ATM-related crimes). A striking example was the situation in Germany, where 496 ATM explosions were recorded in 2022 — an all-time high. In 2023, the number of such incidents worldwide exceeded 18,000.Financial losses from attacks continue to grow both globally and regionally. By the end of 2023, global direct losses to banks from ATM fraud reached US $2.4 billion. Europe lost €173 million during the same period , €67 million of which came from skimming-related attacks. The problem remains particularly acute for the United States: despite accounting for only 25.29% of global transaction volume, American banks incurred 42.32% of global losses. This disproportion is due to the fact that traditional fraud methods, such as skimming, remain a significant threat in many countries. In 2023, 45% of all ATM fraud cases were related to skimming, resulting in losses of over US $900 million in North America alone. More than 315,000 cards were compromised, affecting at least 3,000 financial institutions.

The increasing activity of criminals is naturally driving growth in the ATM security solutions market. According to the Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Security Global Market Report 2025, the global ATM cybersecurity market has grown from $17.77 billion in 2024 to $18.91 billion in 2025, with a compound annual growth rate of 6.4%. Experts attribute this growth to several factors: the increasing number of ATMs worldwide, the increasing sophistication of cyberthreats, and stricter regulatory requirements for financial services security.

However, the approach to device security remains uneven. Physical security measures remain a priority for many banks, while protecting the underlying hardware — operating systems, drivers, and control software logic — often falls by the wayside. This creates serious risks: according to a 2022 study by RTM Group, it's possible to penetrate an ATM without activating an alarm in every other case, allowing an attacker to interact with the equipment unhindered. Underestimating these logical risks leaves many devices vulnerable to attacks that require little skill and can cause significant damage in a short period of time.

Meanwhile, financial technology is constantly evolving, fueling new attacks: in the US alone, losses from cryptocurrency ATM fraud in the first half of 2024 amounted to $65 million. In the face of rapidly evolving threats, a comprehensive approach to ATM security, combining physical and software protection measures, is becoming essential to ensure the resilience of the financial infrastructure.

How an ATM works

To better understand attack vectors, it's important to understand the structure of an ATM and the processes that occur during its normal operation. In this article, we'll examine the user interaction process with the ATM using the example configuration shown in the diagram below.It's worth noting that the diagram describes a specific case discussed in this article and does not represent the default configuration, which may vary from device to device. Now let's examine each stage in the diagram, from card presentation to withdrawal or deposit. To do this, we'll imagine each stage as a separate level of ATM operation, each with its own set of tasks.

1. User level (input devices and kiosk application)

For convenience, individual components and internal processes of an ATM can be thought of as operating at different levels.

User interaction with the device is limited to presenting a card and selecting a transaction. Previously, the only way to access an ATM was by inserting a card into the card reader. Back then, attacks aimed at intercepting card data, such as skimming and shimming (the obtained information was used by criminals to create duplicate payment cards), were widespread. Today, such methods have become largely obsolete in Russia thanks to the implementation of additional security mechanisms and the decline in the percentage of ATMs vulnerable to these attacks.

With the spread of contactless cards, ATMs have added NFC (near-field communication) readers to their card readers. Some ATMs even eliminate the need for a card: a one-time QR code is used, either generated on the ATM screen and scanned in the bank's mobile app, or generated in the app and scanned by the ATM.

To protect against unauthorized access to the card, a PIN code is additionally requested. The PIN code is entered using an encrypted PIN pad (or keypad), which consists of a keypad and a cryptographic module. This ensures that the PIN code is not transmitted or stored in plain text. Verification of the PIN block (the encrypted PIN code value) is performed by the processing center. It is worth noting that modern ATMs that implement mini-office functionality (more on this below) may additionally verify the customer's identity before processing — for example, using biometric modules of facial recognition technology.

After verifying the customer's identity, the ATM prompts the user to select a transaction: cash withdrawal, balance view, funds transfer, or other. Although the ATM contains a standard computer, the user cannot fully interact with it. All necessary functions are provided by a single full-screen banking app running in kiosk mode.

2. OS level (control software and security tools)

As mentioned earlier, an ATM is housed within a standard computer. Let's examine the processes that occur at this level, without discussing the cash dispensing equipment for now.

The part of the ATM that houses the computer is called the service area. This area is separated from the outside world by a flimsy door secured with a simple lock. However, devices of the same series often use a single key, which can be purchased online.

In addition to the system unit, the ATM's service area houses network equipment and connections for the ATM's peripheral devices (card reader, readers, PIN pad, and dispenser). Communication between the peripheral devices and the system unit is via USB, Ethernet, PCI, or COM interfaces.

ATM computers most often run Windows. While Windows Embedded was previously the predominant operating system, Windows IoT (based on Windows 10 and used in embedded systems) is now more common. Furthermore, as part of import substitution efforts, an increasing number of ATMs are being converted to Linux-based operating systems.

A Windows ATM (source: Reddit)

In addition to the banking application running in kiosk mode, the OS also includes ATM management software and security features, such as:

- antivirus software;

- software launch control tools (such as Windows AppLocker) that restrict the execution of third-party programs;

- A VPN client used to establish a secure connection to remote nodes within a bank's internal network.

A key component at the OS level is the control software (CSS). Previously, CSS was developed by ATM manufacturers, which led to compatibility issues when using equipment from different vendors in a single fleet. However, with the spread of the CEN/XFS hardware management standard (more on this below), universal solutions have emerged that allow for the management of devices from different manufacturers. Currently, most ATMs use multi-vendor CEN/XFS-based CSS, which ensures the best compatibility and enables unified maintenance of a diverse fleet of devices.

Although the primary functions of the ATM management system are managing ATM peripherals and interacting with the processing center, depending on the implementation, it may include a number of additional features. For example, it may include software for a monitoring server, which allows for remote management of the self-service device network. To facilitate physical ATM maintenance, additional features (such as quick access to diagnostic utilities from a separate menu) can be implemented in supervisor mode, accessible only to technical staff.

3. Network level (data exchange with the processing center and remote monitoring server)

After selecting an operation, it's necessary to check its feasibility. The decision is made by the processing center — a server on the bank's internal network that checks:

- card details and the correctness of the entered PIN code, which is requested again before performing the operation;

- no restrictions on the selected card;

- user's balance of funds.

To prevent interception and modification of the processing center's responses, data exchange between the processing center and the ATM is protected by encryption, most often using a VPN connection. NDC or DDC are often used as the messaging protocol, having become the unofficial standard for communication with the processing center even before the advent of multivendor UPR. Furthermore, the ISO 8583 standard and its modifications are also widely used. It's worth noting that UPR vendors can develop their own protocols for data exchange with the processing center, while maintaining support for standard protocols to ensure backward compatibility.

In addition to the processing center, the ATM can communicate with a monitoring server, which is used for remote management, device status monitoring, and downloading updates. Unlike communication with the processing center, this type of communication is often not encrypted.

4. Firmware level (data exchange with equipment)

After receiving confirmation from the processing center, the UPO initiates data exchange with the cash dispenser or the cash acceptance module (depending on the selected transaction). At this level, interaction occurs with devices that, in the vast majority of ATMs, are located in the most secure area — the safe area. In addition to the dispenser, the safe may also house a recirculation module (in some cases, this equipment is partially located in the service area). Unlike the service area, which houses the rest of the peripheral equipment, the safe area is made of more durable materials and has a separate key.

A dispenser (without cassettes) in an ATM safe (source: LiveJournal)

Hardware management is implemented according to the CEN/XFS standard, which describes a client-server architecture consisting of a hardware manager (XFS Manager) and service providers (Service Providers). The hardware manager API is implemented by the UPO, and a service provider is a driver containing a set of standard functions for managing and retrieving information about a peripheral device — for example, a dispenser, card reader, or cash acceptance module.

To dispense cash, the dispenser selects the required number of bills from the ATM cassettes, moves them to the cash tray, and opens the shutter (a flap that restricts access to the cash tray). Data transmitted between the ATM and the dispenser can be encrypted, and authentication is performed before the exchange to prevent device substitution. Encryption and authentication algorithms are implemented by the dispenser's built-in firmware.

When cash is deposited, banknotes are verified by a validator. This procedure is especially important for ATMs with a recirculating function, which constitute the majority of the ATM fleet. Unlike traditional machines that only dispense cash, these ATMs can recycle banknotes previously deposited by other users. This increases the importance of accurately detecting counterfeit bills.

Classification of ATM attacks

Now that the design and operation of an ATM are better understood, we can take a closer look at the threats associated with these devices. The wide range of possible attacks on ATMs can be divided into two broad categories based on the target and the nature of the attacker's attack: physical and logical.Physical attacks are aimed at directly affecting the ATM or its components. The goal is to extract funds or interfere with the normal operation of the device without resorting to software. These are traditional attacks that ATMs have been subjected to long before the advent of targeted malware. These attacks require no specialized knowledge, and some target not the ATM itself, but its users.

Unlike physical attacks, logical attacks require specialized skills and greater technical expertise from the perpetrator: they exploit vulnerabilities in the ATM software and its network environment. Despite their complexity, these attacks attract less attention and allow repeated attacks on the compromised ATM to re-profit, making them the most dangerous for banks.

The job of security analysts is to identify software vulnerabilities that enable logical attacks. Therefore, in this article, we won't focus on physical attacks, but will instead focus on logical attacks. These are divided into two categories: system and network.

System attacks are aimed at exploiting functions or altering the logic of applications running on the ATM operating system. The goal of such attacks is to extract funds or bypass security mechanisms. Blackbox attacks are particularly common: while most attacks in this category require the hacker to first gain access to the operating system, a blackbox attack involves connecting the attacker's device directly to the dispenser. It's important to note that blackbox attacks can also be carried out on other ATM peripherals (for example, the banknote validator). This article will focus specifically on interaction with the dispenser.

Network attacks target ATM network components. Hackers may attempt to intercept, forge, or otherwise manipulate data transmitted over the network, or gain remote control over the ATM. The greatest danger comes from attacks targeting the processing center: if security is inadequate, a hacker can forge responses sent to the ATM and perform cash withdrawals even if they were rejected by the processing center.

It's important to understand that most system and network attacks require access to the equipment in the ATM's service area. During a security assessment, security specialists are granted this access by default; a hacker can gain access by drilling a hole in the ATM's casing or by picking the lock on the service area door. It's also important to remember that a key to the service area can sometimes be purchased online or obtained from an insider — for example, a technical engineer who maintains the ATM's equipment.

Only some of the attacks described result in cash withdrawals; the remaining attacks represent intermediate steps toward this goal. For example, an attacker might seek to gain remote control of an ATM over the network and then develop an attack at the OS level using methods classified as system attacks. A matrix can be used to represent the interrelationships, reflecting the possible transitions between attacks that would allow for a complete cash withdrawal scenario.

Below is an example of such a matrix: an arrow in a row indicates the transition to an attack in the corresponding column, and a check mark reflects the possibility of the attacker receiving funds as a result of the attack.

Here's how you can use the matrix to build a money disbursement scenario:

- Exiting kiosk mode itself doesn't result in the disbursement of funds, but it is an intermediate step. It may be followed by exploitation of OS and software vulnerabilities, bypassing local security policies, or exploiting network configuration flaws (for example, a hacker might attempt to dump the VPN client configuration after gaining access to the OS).

- In turn, exploiting OS and software vulnerabilities can lead to the theft of funds — for example, if the UPR contains flaws. Furthermore, this attack can also serve as an intermediate step: for example, if the VPN client being used has vulnerabilities, an attacker can gain access to secure network traffic and intercept transmitted data.

Some columns lack arrows, indicating that a hacker only needs access to the ATM's service area to carry out an attack. For example, accessing the hard drive requires no additional steps: this action could be the first step in a full-fledged theft vector.

A matrix can provide a general idea of possible cash dispensing scenarios, but the real fun lies in the details. Therefore, in the next chapter, we'll examine the most common ATM attacks encountered by our banking security researchers.

(c) Source