Carding 4 Carders

Professional

- Messages

- 2,724

- Reaction score

- 1,578

- Points

- 113

Hackers, crooks, IT security workers, investigative agencies and special services - all of them, under certain circumstances, can try to get to information protected by passwords. And if the tools used by hackers and special services, on the whole, practically coincide, then the approach to the task differs radically. Except for isolated cases, which can be resolved with enormous efforts, the expert works within the framework of strict restrictions both in terms of resources and in the time that he can spend on cracking a password. What approaches are used by law enforcement agencies and how they differ from the work of hackers is the topic of today's material.

With a kind word and a pistol

Of course, first of all, representatives of the security agencies act by persuasion. “You will not leave here until you unlock your phone,” they say to the detainee, placing a document in front of him, where it is written in English and white that “the bearer of this has the right to inspect the contents of mobile devices ”of the detainee. The only thing that the detainee is obliged to unlock his own phone is not a word in the document. That does not prevent the security agencies from shamelessly exercising the right they do not have.Is it hard to believe this? In fact, not really: the last such incident happened just the other day. US citizen Sidd Bikkannavar, who works for NASA, was detained at the border while entering the country; it was by “word and gun” that he was persuaded to unlock his corporate smartphone.

Yes, you don't have to testify against yourself and give out your passwords. This principle is clearly illustrated by another case. The suspect in possession of child pornography has been imprisoned for 16 months for refusing to provide passwords for encrypted disks. Presumption of innocence? No, you haven't heard.

However, such measures can not always be applied and not to everyone. A petty swindler, a marriage swindler or just a fan of pumping up music "in reserve" without intelligible evidence cannot be banned in prison, as well as a serious criminal with money and lawyers. The data has to be decrypted, and the passwords have to be opened. And if in cases related to grave crimes and a threat to national security (terrorism), the hands of experts are untied, and there are practically no restrictions (financial and technical), then in the remaining 99.9% of cases the expert is severely limited both by the available computing capabilities of the laboratory, as well as and time frames.

And what about this in Russia? At the border, the devices are not forced to be unlocked yet, but ... I will quote an expert who is engaged in extracting information from the phones and computers of detainees: "The most effective way to find out the password is to call the investigator. "

What can be done in 45 minutes? And in two days?

Films don't always lie. At one of the exhibitions, a man approached me, in whom I immediately recognized the head of the police station: big, bald and black. The information from the token confirmed the first impression. “I have two hundred of these ... iPhones in my area,” the visitor began immediately. "What can you do in 45 minutes?" I have never encountered such a formulation of the question before. However, at that time (three years ago) devices without a fingerprint scanner were still popular, Secure Enclave had just appeared, and, as a rule, there were no problems with the installation of a jailbreak. But the question stuck in my head like a thorn. Indeed, what can be done in 45 minutes? Progress is underway, defense is becoming more complicated, and the police are running out of time.In the most insignificant cases, when a user's phone or computer is confiscated “just in case” (for example, they were detained for petty hooliganism), the investigation will have neither the time, nor the energy, nor, often, highly qualified employees to crack the password. Failed to unlock your phone in 45 minutes? Let's turn to the evidence collected in a more traditional way. If you fight to the last for every encrypted device of every petty hooligan, there won't be enough resources for anything else.

In more serious cases, when the suspect's computer is also confiscated, the investigation may make more serious efforts. Again, the amount of resources that can be spent on hacking will depend on the country, on the severity of the crime, on the importance of digital evidence.

In conversations with police officers from different countries, the figure “two days” most often arose, while it was understood that the task fell on an existing cluster of a couple of dozen computers. Two days to break passwords that protect, for example, BitLocker encrypted containers or documents in the Office 2013 format - isn't it too little? It turns out not.

How do they do it

The police had tools for cracking passwords from the very beginning, but they learned to use them fully not so long ago. For example, the police have always been interested in passwords that can be retrieved from a suspect's computer, but they retrieved them first manually, then using single utilities that could, for example, get only a password from ICQ or only a password to accounts in Outlook. But in the past few years, the police have come to use all-in-one tools that scan the hard drive and Registry devices and save all the passwords they find to a file.In many cases, the police use the services of private forensic laboratories - this applies to both routine and high-profile cases (a thick allusion to the trial in San Bernardino). But the "private traders" are ready to use the most "hacker" methods: if the original data does not change, and there are no traces of interference, then the way in which the required password was obtained does not matter - in court an expert may refer to a commercial secret and refuse to disclose technical details of hacking.

Real stories

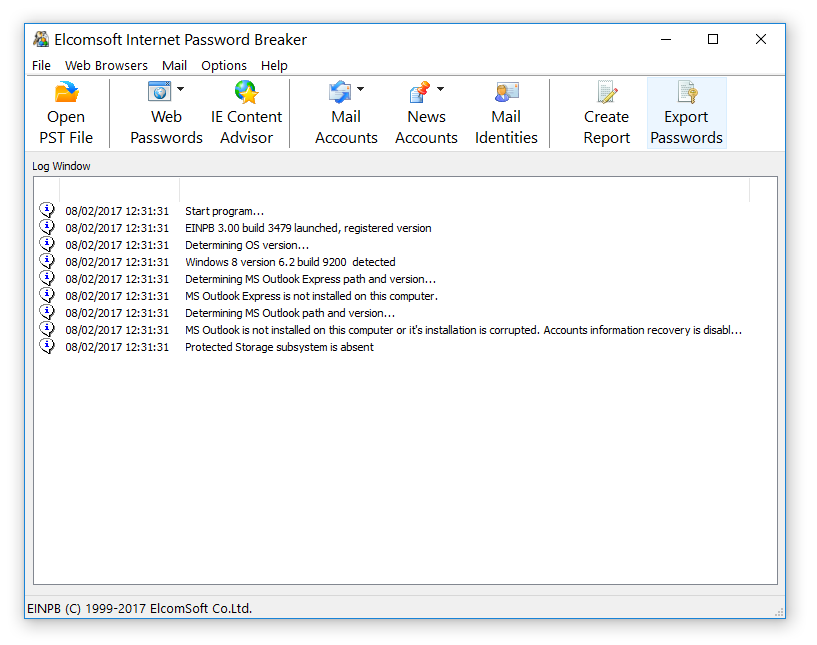

Sometimes you need to act quickly: it's not about resources, it's about time. So, in 2007, the laboratory received a request: a 16-year-old teenager was missing. The parents turned to the (then) police, who came to the laboratory with the missing person's laptop. The laptop is password protected. It was clear that there were no months to brute force passwords. Work on the chain started. The disk image was taken, in parallel, an attack on the password was launched in Windows. Searching for passwords on the disk has started. As a result, an email password was found in Elcomsoft Internet Password Breaker. There was nothing more interesting on the computer. There was nothing in the mail that could help in the search, but through the mailbox it was possible to reset the password to ICQ, and there correspondence with friends was found, from which it became clear to which city and to whom the teenager "disappeared". Ended up safely.However, stories do not always end well. A few years ago, a French private investigator contacted the laboratory. The police asked for his help: a famous athlete disappeared. I flew to Monaco, then the traces are lost. At the disposal of the investigation was the athlete's computer. After analyzing the contents of the disk, iTunes and the iCloud control panel were found on the computer. It became clear that the athlete had an iPhone. We tried to access iCloud: the password is unknown, but the authentication token (pulled from the iCloud Control Panel) worked. Alas, as is often the case, the cloud backup did not contain any hints of the location of the "lost", and the backup itself was created almost a month and a half ago. Careful analysis of the contents revealed the password for the mail - it was saved in the notes (the same "

But back to our two days for the hack. What can be done during this time?

How (im) useful are strong passwords

I have no doubt you have heard advice many times on how to choose a "strong" password. Minimum length, letters and numbers, special characters ... Is it really that important? And will a long password help protect your encrypted volumes and documents? Let's check!First, a little theory. No, we will not once again repeat the mantra about long and complex passwords, and we will not even advise using password savers. Let's just look at two pictures:

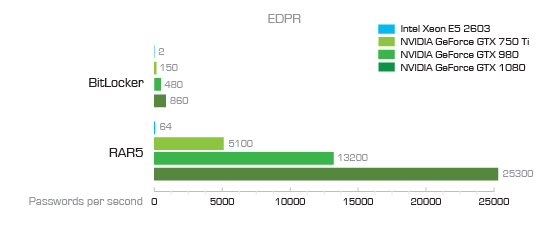

Password brute-force speed using a video card: here is BitLocker and RAR5

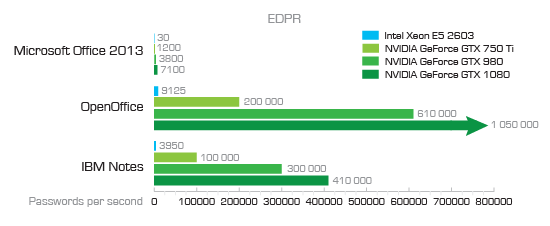

Microsoft Office, Open Office and IBM Notes

As you can see, the brute-force speed for BitLocker volumes is only 860 passwords per second when using a hardware accelerator based on Nvidia GTS 1080 (by the way, this is really fast). For Microsoft Office 2013 documents, the figure is higher, 7100 passwords per second. What does this mean in practice? Something like this:

Thus, on a very fast computer with a hardware accelerator, a password consisting of five letters and numbers will be cracked in a day. If the same five-digit password contains at least one special character (punctuation mark, # $% ^ and the like), it will take two or three weeks to break it. But five signs are not enough! The average password length today is eight characters, which is far beyond the computational capabilities of even the most powerful clusters at the disposal of the police.

Nevertheless, most passwords are still broken, and it is in two days or even faster, regardless of the length and complexity. How so? Do the police, like in the movies, find out the name of the suspect's dog and the year of birth of his daughter? No, everything is much simpler and more efficient, if we talk not about each individual case, but about statistical indicators. And from the point of view of statistics, it is much more profitable to use approaches that work in "most" cases, even if they do not give results in a particular case.

How many passwords do you have?

I calculated: I have 83 unique passwords. How unique they really are is a separate conversation; for now, just remember that I have 83. But the average user has much fewer unique passwords. According to surveys, the average English-speaking user has 27 online accounts. Can such a user remember 27 unique, cryptographically complex passwords? Statistically - not capable. About 60% use a dozen passwords plus their insignificant variations (password, password1, well, so be it - Password1234 if the site requires a long and complex password). This is shamelessly used by the special services.If there is access to the suspect's computer, then extracting a dozen or two passwords from it is a matter of technique and a few minutes. For example, you can use Elcomsoft Internet Password Breaker, which extracts passwords from browsers (Chrome, Opera, Firefox, Edge, Internet Explorer, Yandex) and email clients (Outlook, Thunderbird and others).

In it, you can simply browse through the password stores, or you can click Export, as a result of which, in a matter of seconds, all available passwords will be extracted from all supported sources and saved to a text file (duplicates are deleted ). This text file is a ready-made dictionary, which is later used to crack passwords that encrypt files with serious protection.

Extracting passwords from browsers and email clients

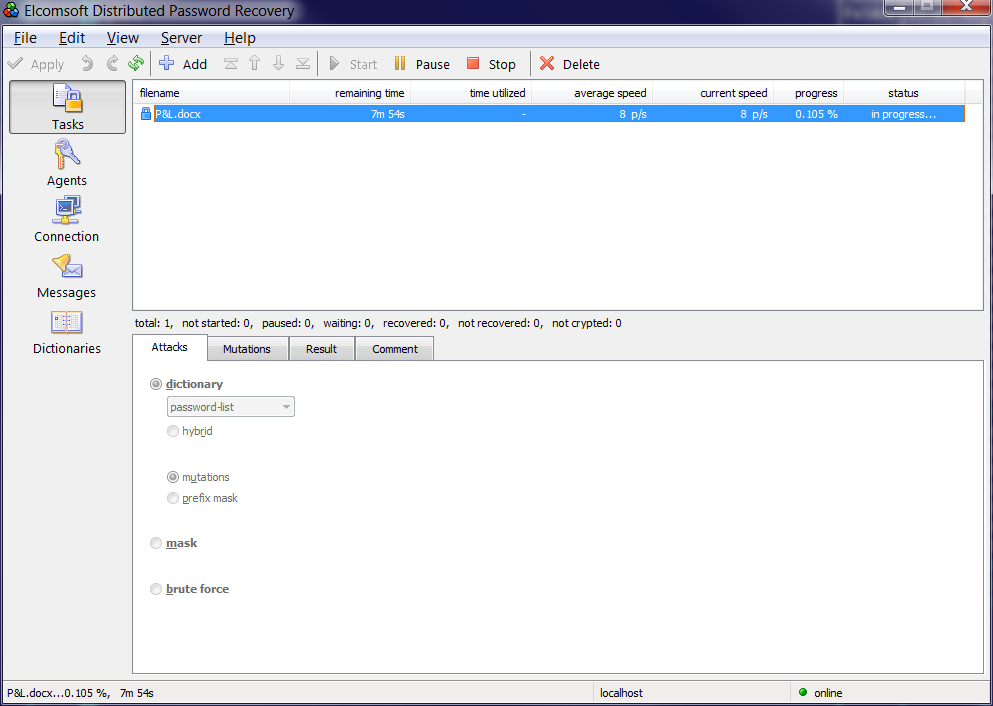

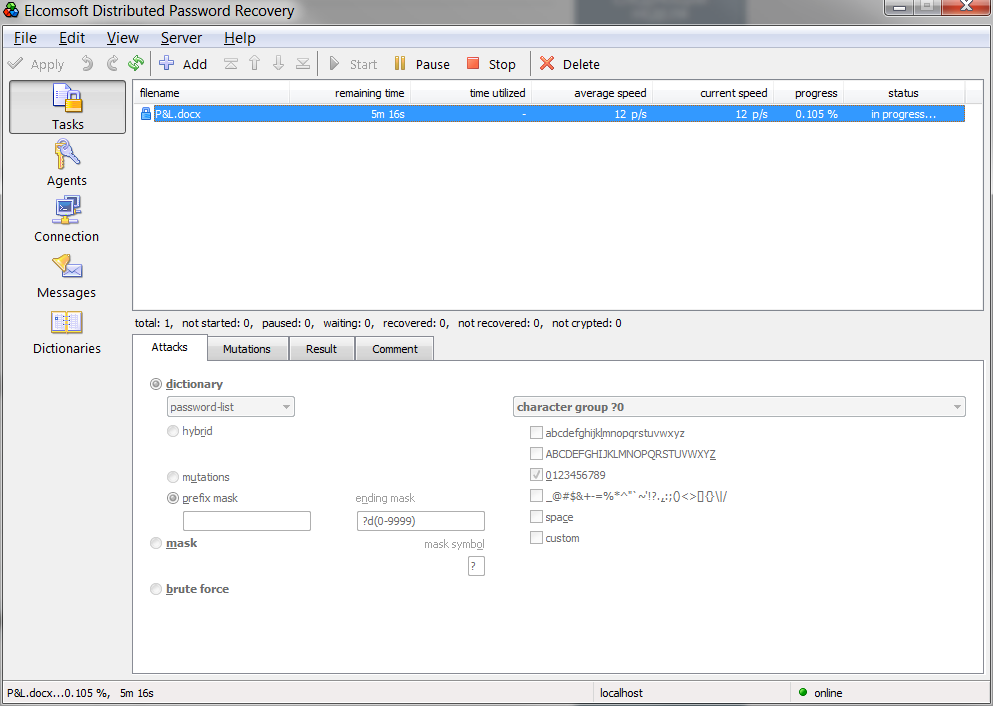

Let's say we have a P & L.docx file extracted from a user's computer, and there is a dictionary of his passwords from several dozen (or even hundreds) of accounts. Let's try to use passwords to decrypt the document. Almost any password brute-force program that supports the MS Office 2013 document format can help with this. Elcomsoft Distributed Password Recovery is more familiar to us.

The attack takes place in three stages. At the first stage, we simply connect the dictionary “as is”.

This stage takes a split second; the probability of success “here and now” is about 60% for the average user (not a hacker, not an IT specialist or a cybercriminal).

The second stage - the same dictionary is used, consisting of user passwords, but numbers from 0 to 9999 are appended to the end of each password.

Finally, the third stage is the same document, the same vocabulary, but variations are run (“mutations” in EDPR terminology). The screenshot shows a list of available mutations:

It is tempting to activate all of them, but there is little practical sense in this. It makes sense to study exactly how a particular user chooses his passwords and what variations he uses. Most often these are one or two uppercase letters (medium case variation), one or two digits in arbitrary places of the password (medium digit variation) and the year, which is most often appended to the end of the password (medium year variation) ... However, at this stage, it still makes sense to look at the user's passwords and take into account the variations that he uses.

In the second and third stages, every tenth password is usually broken. The final probability of the average user decrypting a document is about 70%, and the attack time is negligible, and the length and complexity of the password do not matter at all.

Exceptions to the rule

If one user has files and accounts protected by the same passwords, this does not mean that he will be so lucky every time. For example, in one case, a suspect stored passwords in the form of contact names in the phone book, and in another, a collection of passwords matched the names of encrypted files. Once again, the files were encrypted with the names of the suspects' resting places. There are simply no tools to automate all such cases: even the file name has to be manually saved by the investigator in the dictionary.Length doesn't matter

When it comes to the length and complexity of passwords, most users are not used to bothering themselves. However, even if almost everyone used passwords of the maximum length and complexity, this would not affect the speed of the attack using leaked dictionaries.If you're following the news, you've probably heard of password database leaks from Yahoo (three times in a row!), LinkedIn, eBay, Twitter, and Dropbox. These services are very popular; in total, tens of millions of accounts have leaked. The hackers did a gigantic job, recovering most of the passwords from the hashes, and Mark Burnett put all the leaks together, analyzed the situation and made interesting conclusions. According to Mark, there are clear patterns in which passwords are chosen by English-speaking users:

- 0.5% use the word password as a password;

- 0.4% use the password or 123456 sequences as a password;

- 0.9% use password, 123456 or 12345678;

- 1.6% use a password from the ten most common (top-10);

- 4.4% use a password from the first hundred (top-100);

- 9.7% use a password from the top-500;

- 13.2% use from the top-1000;

- 30% use out of top-10000.

What does this information give us? Armed with statistics and a dictionary of 10 thousand of the most common passwords, you can try to decrypt the user's files and documents even in cases when nothing is known about the user himself (or it was simply not possible to access the computer and extract his own passwords). Such a simple attack using a list of only 10,000 passwords helps the investigation in about 30% of cases.

70 + 30 = 100?

In the first part of the article, we used a dictionary made up of the user's passwords (plus small mutations) for the attack. According to statistics, this attack works about 70% of the time. The second method is to use a list of top 10,000 passwords from online leaks, which gives, again statistically, a 30 percent success rate. 70 + 30 = 100? In this case, no.Even if the "average" user uses the same passwords, even if these passwords are contained in leaks, there is no question of any guarantee. Offline resources, encrypted volumes and documents can be protected by fundamentally different passwords; the probability of this has not been measured. When investigating crimes related to computers, the likelihood of running into a user who does not fall into the "average" category increases markedly. It is not entirely correct to say that 30% or 70% of any user's passwords are revealed in a few minutes (a priori probability). But you can report about seventy percent disclosure (posterior probability).

It is precisely such fast, easily automated and well predictable methods that law enforcement agencies like to use if the “good word and the gun” do not work.

That's all?

Of course, the process does not stop at the listed attacks. Own dictionaries are connected - both with popular passwords, and dictionaries of English and national languages. As a rule, variations are used, there is no single standard here. In some cases, they do not disdain the good old brute force: a cluster of twenty workstations, each of which is equipped with four GTX 1080s, is already half a million passwords per second for the Office 2013 format, and for archives in the RAR5 format even for two million. It is already possible to work with such speeds.Of course, account passwords that can be retrieved from a suspect's computer will not always help in decrypting files and encrypted containers. In such cases, the police do not hesitate to use other methods. For example, in one case, investigators encountered encrypted data on laptops (system drives were encrypted using BitLocker Device Protection in conjunction with the TPM2.0 module).

It is useless to attack this defense "head-on"; the user does not set any password in this case. The analysis of another device, to which the user logged in using the same Microsoft Account, helped. After recovering the password for Microsoft Account, decrypting the system drive became a matter of technology. In another case, data from encrypted laptops was found unprotected on the server.

How to protect yourself? Audit your passwords first. Try to do everything that we showed. Did you manage to crack the password for a document, archive, encrypted volume in a few minutes? Draw conclusions. Failed? Nobody canceled the methods of soft persuasion.

(c) xakep.ru